Even though it seems like months ago that I biked through Kansas, I’ve only been out of my home state for a few weeks. When I entered Kansas, I could have taken a 230 mile direct route due north, limiting my exposure, but instead (not quite ready to give up on Kansas) I zigzagged a 550 mile route with 14 presentation stops through the sunflower state, giving me plenty to write about. In fact, I had all the intentions in the world to write about my Kansas miles in a relevant time frame, but since I’ve now put a healthy distance between me and my home state I’ll have to rely on my memory.

Welcome to Kansas! Taking this photo could have been the most dangerous thing I've done yet.

Relying on memory is hardly reliable. The truth is, I’ve already forgotten many miles of Kansas. Well, maybe forgotten is the wrong word. Maybe it is more like most of the miles have run together. A mash of pasture lands, farm lands, and showboating clouds, connected by a montage of roadsides mowed and roadsides wild with milkweed and monarchs. There are moments of clarity in my memory of miles. I clearly remember hooting as tail winds blew me forward, and the moment when I took off my rain gear and let my skin breathe fresh sun after days of rain. I remember each still-living snake, turtle, and frog on the road that I scolded, photographed, and transplanted. But mostly my time biking bleeds into an impression, and what I remember are the people I met, the schools I stopped at, and the odd ball/darn tough moments.

So really, bike touring is like life. I remember the challenges, the friends, and the strange, unpredictable moments that come from taking risks. Boring days, easy days, risk-free days seem like lost days; days that slowly slip through the holes of my memory, and dissolve into the fabric of my time. Those experiences are still there, changing my perspectives and path, but absorbed in my story so completely I’ll never be able to isolate them once again. And even though Kansas is just a week gone, I feel my brain sorting out the memories I’ll carry in details and the memories that will blend into the background.

This is what a lot of miles in Kansas look like.

This is what I think will stick:

As soon as I crossed the border I started heading due west. Heading west always feels purposeful and cinematic for me, and I wonder if the draw I feel to go west at all resembles the monarchs’ draw to Mexico. But this time I was headed west just to get to Wichita, KS for presentations, and then I reversed course and started heading east.

When I left Wichita it was rainy and had been raining for several days. The winds had churned up the kind of storms people talk about. I overheard a group of motorcyclists planning a route change, going out of their way a few hundred miles to the south, to avoid storms. I didn’t have that luxury, and so I donned my rain gear and aimed east to the storm.

The Great Plains Nature Center hosted ButterBike, butterflies, and lots of wild space in the center of Wichita, KS.

Turns out my route east was no big deal. In fact, guardian angel like winds, ushered me forward, and I was gifted with tailwinds that nearly doubled my average speed of 10mph. If you could ignore the rain, and if you didn’t stop long enough to get cold, you could practically call those eastward miles perfect. Riding with the unfought wind, invisible, and quiet on my back, compelled me to cheer progress on. I hooted at gawking cows bored with my freedom, and hee'ed and hawed at roadside grasses waving like crazed fans. If you have never ridden a bike through lonely country like a cowboy with a purpose, then you of course probably don’t get the point in biking. The point is this: to ride unencumbered, more than human, strong and powerful, like an animal on Earth. Tailwinds are magic. I don’t easily forget them.

TAILWINDS in Kansas...

The tailwinds blew me straight to Pleasanton, KS, dumping me like a wet, cold dog on the steps of Jenny’s house. As the school lunch lady at the school I would be visiting the next day, Jenny worked her magic and prepared a meal big enough to feed a school, and I ate enough to feed a class. This would be the first night of hospitality in a string of nights that would lead me through the state and into Missouri. It also began a string of school visits and media interviews that would get me as close to famous as I have ever come.

The first stop in this string of visits was in Pleasanton, KS, which sits on the eastern edge of the state. To the north lies Louisburg, staving off the winds and the advances of Kansas City’s suburbs. In between the small towns of Pleasanton and Louisburg, you’ll find smaller towns and the Marais des Cygnes National Wildlife Refuge.

Marais des Cygnes National Wildlife Refuge sits between Pleasanton and Louisburg, KS and was a great stop on my trip.

Besides having a nearly unpronounceable name, Marais des Cygnes National Wildlife Refuge (mare de ceen is the pronunciation I went with) is a refuge for monarchs and humans alike. Refuges have become life rafts floating in a world where humans, in such a short time, have nearly erased the prairie, the milkweed, and the monarch from our planet. These pockets protect species most of us will never learn to identify but serve to make our planet special. And these refuges protect me. They protect me from the boredom and surfacing doom that accompanies biking through nothing but monoculture farms, and they offer me quiet roads with little traffic. A bubble of safety to let my heart rate settle before heading back out to a less pleasant reality.

The refuge system has been a spectacular resource for me, and the contacts I have made have allowed me to visit, present at, and enjoy some wild beauty as I migrate with the monarchs. When I am on these lands I see more milkweed, more monarchs, and have more hope. The refuge system is less glamorous than the National Parks, but their humbleness allows for a more casual and thus more intimate connection to our neck of the woods nature. If you have never visited a wildlife refuge near your home, then you are missing out on great opportunities. And even if you never visit, be glad that they are there, doing their job quietly so the future might be able to visit the wild too.

Go visit your local national wildlife refuge and enjoy knowing that these pockets of protection are where wild still lives.

My connection to the refuge system was thanks to the refuge manager at Marais Des Cygnes, Patrick Martin. He saw the potential of my trip to connect communities to nature, science, stewardship, and the refuge system, and he put himself to work contacting local schools, the media, and staying so organized I didn’t have to! During my stop over at his house, we had feasts, a bonfire, a gloriously snakey stroll, and many route planning sessions for all my excursions. His hard work yielded four school visits, a milkweed garden planting, three newspaper interviews, and a visit from the Kansas City nightly news tv crew.

Patrick Martin helped make school presentations like this one ANDgarden plantings, and media interviews possible.

Patrick also helped a school in Pleasant apply for free milkweed starts from Monarch Watch, and I got to help with the plantings.

The momentum of the local media coverage spearheaded by Patrick followed me to Kansas City, creating a buzz that left me thinking I wouldn’t be able to handle actual fame. Being a spokesperson is exhausting. I have happily gone days without talking to anyone, and there I was talking to everyone. But this of course was the point. The only way to be a voice for the monarch is to talk, and talk, and talk. So I talked to newspapers, I talked to tv reporters, and got to talk on the radio.

Besides talking with reporters I got to catch up with family, and meet the new additions, including two baby humans AND lots of monarch caterpillars.

As a super fan of NPR, speaking into a microphone on KCUR, Kansas City’s NPR radio station was a highlight of my Kansas City visit. NPR correspondents have brought me stories from every corner, and their familiar voices are like friends on the road. In our internet world, where so much information is chosen for its price rather than its content, I was so proud to not just pay for less-sensationalized news but actually be part of that day’s news. So I donned my headphones, cleared my throat, gamed out some jokes (my bike has a face for radio seemed too predictable) and was another NPR voice! That 20 minutes was great practice for my not-yet-scheduled-but-often-daydreamed-about interview with Terry Gross (hint hint hint) and my not-yet-scheduled-but-often-daydreamed-about intellectual musings with Guy Ross (hint hint hint).

Speaking of hints. A VERY tangential hint. Many people tell me that I am brave for doing a trip like this. To those people my advice includes NOT watching the nightly news on TV. Nightly news uses canned police lights, dramatic mug shots, flashing warnings, and devastated news anchors to keep us watching. The by-product of this, I believe, is that we grow more and more scared of our world, and rely more and more on news’ special effects, rather than our own experiences to define the world for us. NPR’s business model and inability to throw scary photos in our faces give us the power to process news more critically and pragmatically. If you can’t stop watching, at least note the drama and give it perspective.

Okay. Radio rant, check.

My forth grade teacher, Connie. Yeah she said I could call her by her first name.

Another highlight of Kansas City was talking with kids at six area schools. In Kansas, with a presentation I have been tinkering with since Texas, I felt like I hit my stride and was having lots of fun. I had kids going on pretend bike rides, singing like American toads, piling into my tent (to prove just how luxurious and spacious it is), and cheering on milkweed. During my presentations, I also got to see familiar faces in the crowd. Several of the schools I had visited on previous trips, so I knew a few of the teachers and students. At one presentation, the crowd included my grade school classmate (now a teacher) and at another presentation my fourth grade teacher had come to cheer me on. These moments, where we reflect on our path from past to the present, are mind warping and so exciting. Where and when and how will our paths cross again?

I found my stride in Kansas with my presentation and had a lot of fun. Photo credit: Citizens of the World Charter School

Kindergartners in Kansas City "bike" with me and think about what it would be like to go on this trip and not be able to find food. Photo credit: Citizens of the World Charter School

As for paths crossing, this visit to Kansas City, my parents and I didn’t cross paths. Normally when I visit my mom bakes this awesome fake sausage, spaghetti squash casserole and my dad organizes a get together with family and neighbors. This time, they cheered me on from Europe, where they were getting graffiti art project ideas, seeing the iconic and less iconic Europe, chasing potential pickpockets, eating the local fare, and hopefully being distracted enough not to worry about me.

So even though my parents were out of town, I took a week long break at their house, ate plenty of their food, and planned out the next thousand miles of my trip. Their house is just a few blocks from the Missouri, Kansas state line, and I crossed into Missouri many times on my break. From Kansas City, I could have biked north and left Kansas behind, but instead I detoured southwest a hundred miles to Lawrence, KS.

Look mom, the cats are alive, well, and enjoying the fresh air and sunshine.

The detour to Lawrence was well justified. Lawrence is the college town that houses the University of Kansas, famous for Jayhawks in some circles and Monarch Watch in others. My visit centered around Monarch Watch, the organization spearheading monarch waystations (gardens for migrating monarchs and other pollinators) and tagging efforts. My timing, normally not perfect, happened to be impeccable, and I arrived just in time for their open house and plant sale, a super bowl of monarch fans buying plants, talking science, and rallying together. I saw the familiar faces of people that had helped me on my trip and met new folks. In a world of bad news, it was nice to be in the company of people that you can count on to help you fight. A team in this war against losing the monarch.

Monarch Watch sold milkweed to the monarch team: people sharing their yards, speaking for the monarchs, and motivating each other. It was inspiring.

Included in that team is Dr. Chip Taylor, a legend in the monarch world, and the founder of Monarch Watch, an organization that promotes education, conservation, and research of the monarch butterfly. He walks from person to person with monarchs clinging to his white beard. He’s down to earth and takes the time to talk with everyone. Before starting my trip he gave several hours of his time and lots of great advice. Scientist willing to talk to non-scientists and nurture their passion are better scientists. Doing this, he can grow his voice, giving people all over the country the skills and knowledge and tools to be a voice for the monarchs too.

Dr. Chip Taylor, who founded Monarch Watch, an outreach program focused on education, research and conservation relative to monarch butterflies, finds time to talk monarchs with monarch fans.

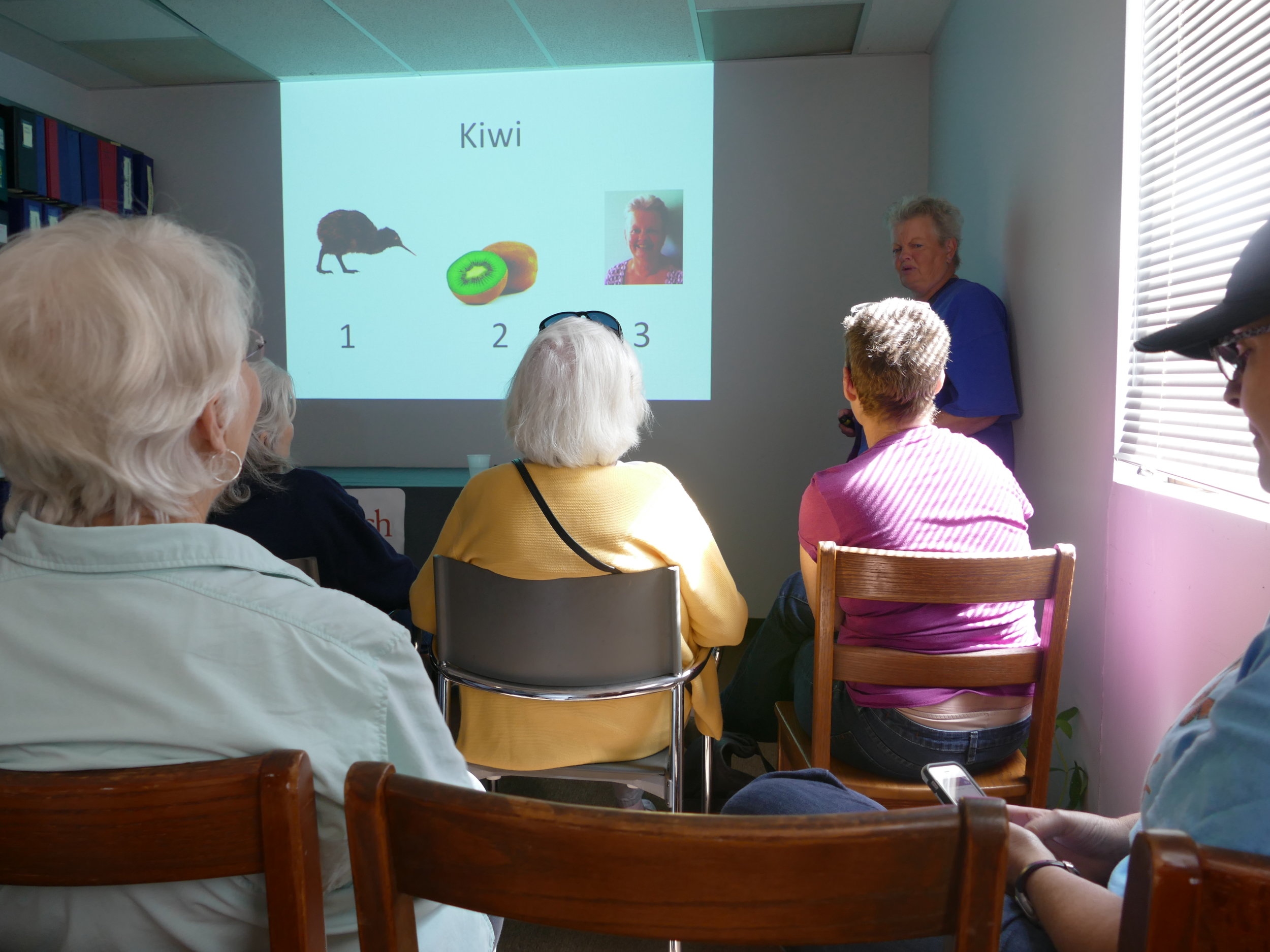

Lots of people are starting conversations and organizations to promote solutions and mindshifts for the monarch. On this trip I am lucky to meet some of them, and use their motivation and dedication to inspire me. At the Monarch Watch open house, I saw friends from Oklahoma and Kansas that were doing more than their share and spreading the passion throughout the United States. I also got to learn from a woman/Kiwi leading butterfly conservation efforts in New Zealand. There is not one way to save the monarch, but all of us have a voice and the ability to start conversations and try.

Jacqui Knight shares lessons from her New Zealand conservation efforts. She has also ridden a horse the length of New Zealand (and survived to write a book about it), which gives me hope for my horse traveling dreams.

Trying is all any of us can do. So in Kansas I biked and taught and talked and tried. And even though my memory might mess up the details or run the miles together, I am grateful for these Kansas miles and have learned a lot as I migrate with the monarchs.

The Indian Creek Garden Club and their dozens of monarchs are proof that trying is what we need to do. These kids and many more, made my Kansas miles memorable.